Hi, folks! In this, the first blog post on my site, I’ll explain a bit about one of my research projects that I’m especially excited about lately. I’ll aim to keep it at a level that is understandable for “non-experts,” but inevitably there will be some astro jargon that creeps in… -Jeff

The sparsely-populated outermost regions of our Milky Way galaxy are poorly studied. In part, this is because stars of a given type become fainter the more distant they are from us – think about a flashlight: if I stand a few feet away from you, it will look pretty bright (you could read a book by its light), while if I’m a block away, it will just look like a small point of light. This is due to what’s often called the “inverse square law,” which says that light from a given source diminishes in intensity proportional to the square of the distance from the viewer (10 times further away means $10^2$, or 100 times, fainter). This means that the old stars in the most distant parts of the Milky Way’s “halo” are quite faint. Furthermore, it’s difficult to estimate the distances to typical stars. So, to study the distant reaches of our Galaxy’s stellar halo, we need stars that:

- are intrinsically bright (so we can still detect them even at large distances),

- are fairly common in old, metal-poor populations such as the Milky Way halo,

- are easy to pick out from among the other, more numerous, types of stars between us and the outer Galaxy, and

- whose distances can be easily estimated.

.)](/img/mw_halo.jpg)

The halo of the Milky Way is the diffuse outer region surrounding the disk, where we live along with most of the gas, dust, and stars in the Galaxy. Although it contains only about 1% of the stars in our Galaxy, the halo gives us vital clues about how the Milky Way has grown and evolved. (Image from Hubblesite.)

RR Lyrae – pulsating variable Stars

For an ongoing project I’m working on, the solution we have adopted is to use RR Lyrae stars. These are a type of variable stars named after the first one to be discovered – the star RR Lyrae. RR Lyrae stars are a type of star whose brightness varies because the entire star is pulsating (growing larger, then shrinking, then growing larger again…). As the star expands and contracts, its brightness changes in a characteristic way, which can be seen in repeated observations of the star (some examples are seen in the header image above, on the right side). (For history of RR Lyrae, including details of their discovery by Williamina Fleming, see this intro at the AAVSO site.) It turns out that the period of this pulsation (the time it takes to complete one “cycle” of expansion/contraction) is related to the intrinsic brightness of the star, so once you know the period, you can compare its average measured brightness with the derived intrinsic brightness and determine how far away the RR Lyrae star is.

.)](/img/M3_color3.gif)

Image of the outer regions of the globular cluster M3. This shows an animation of 4 images of the same field taken over the course of the same night. You can see that most of the stars remain the same as it blinks between the 4 images, but some stars change their brightness with time. Most of these are RR Lyrae variables, which can fairly easily be selected by observing the same field of view multiple times. (Image from this page.)

You can see from the figure above that criterion #3 (“are easy to pick out from among the other, more numerous, types of stars”) is easily satisfied by revisiting the same field repeatedly and determining which stars change in brightness within a few hours. As we mentioned above, the distances to RR Lyrae stars are easily determined once you establish the period of pulsation (#4 above). RR Lyrae stars are indeed fairly bright, and only occur when stars roughly the mass of the Sun (but with much lower abundances of metals) are in the late stages of their lives. Thus they satisfy all of the criteria we laid out above for ideal tracers of the Milky Way halo.

Now, RR Lyrae stars are well-studied, and are used frequently to map the inner parts of the Milky Way’s halo. However, it has only been recently that it has become feasible to observe these pulsating variables in the outermost halo. This is because it requires a large enough telescope to quickly gather enough light from faint, distant stars, that also has a camera with a large enough field of view that we can map large areas of sky in a reasonable time frame. One example is the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) (built for the Dark Energy Survey) on the 4-meter Blanco telescope at CTIO, which we are using for a survey of the outer halo of the Galaxy.

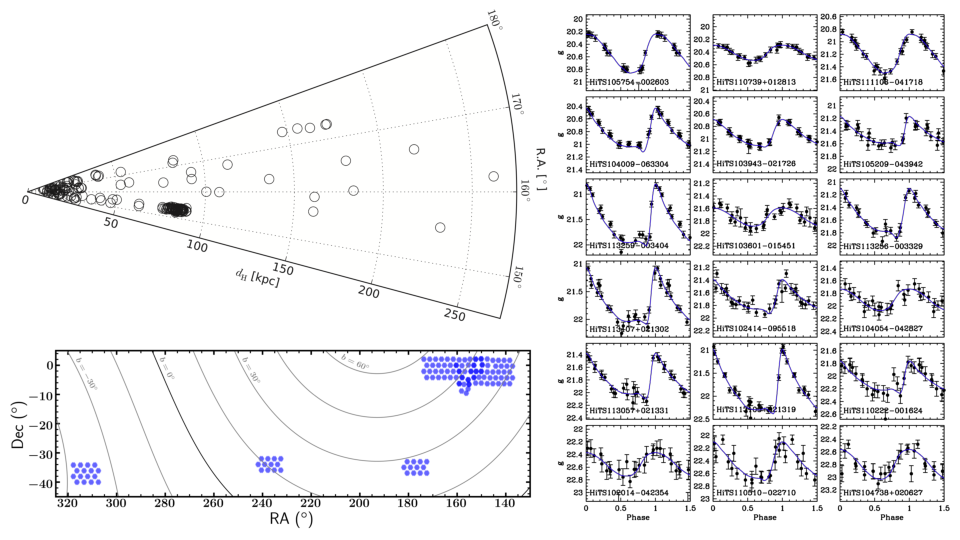

Figures from a paper by Medina et al. (2017) showing first results from our survey. At the right, we show “light curves” (brightness vs. time within the pulsational period, or “phase”) of the most distant RR Lyrae from our survey, with template RR Lyrae curves overlaid. The lower left figure shows regions on the sky that we have observed thus far, and the upper left illustrates the distances ($d_{H}$) as a function of position in a small wedge of sky.

The figure above shows results from our first publication about this project. In that paper, we presented a total of 173 RR Lyrae stars in about 120 square degrees of sky, in 40 DECam fields that were observed 20 times each. About 1⁄3 of these are in the Sextans dwarf spheroidal galaxy, which happens to be within the field of view, another 2 are in the Leo IV dwarf galaxy, and 3 more are newly-discovered variables in the Leo V dwarf galaxy (see this Medina et al. 2017a paper). Of the remaining RR Lyrae, we found 18 that are beyond 90 kiloparsecs (abbreviated kpc; 90 kpc is about 290,000 light years), including the most distant RR Lyrae yet known around the Milky Way at beyond 200 kpc (650,000 light years; we think the “edge” of our Galaxy should be around 250-300 kpc – but that’s one of the things we’re hoping to find out with this study!). We have now obtained DECam observations of 3 times as many fields, and analysis is ongoing. We hope to expand the sample of RR Lyrae stars at the outer limits of the Milky Way to more than 50 (in about 1% of the sky), so that we can begin to infer global properties of the stellar halo of our Galaxy.

This is precursor science in anticipation of (and to develop tools for) the upcoming Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST). LSST will consist of an 8.4-meter optical telescope (currently under construction in Chile), a 3.5-degree diameter field of view, and a 3.2 billion pixel (that’s giga-pixel) camera. The planned survey (starting in 2023) will observe roughly half the night sky repeatedly for 10 years, ultimately imaging each patch of sky hundreds of times with each of 6 filters. This deep survey will revolutionize our understanding of time-varying astronomical phenomena (including variable stars, but also supernovae, active galactic nuclei, and many other objects). In fact, LSST will find RR Lyrae to distances more than 3 times further than we are reaching in our current DECam survey, over more than 50 times the sky area. Stay tuned!

In my next post I’ll explain more about why we want to find these distant Milky Way halo stars.